Special Topic: Aging Population

- Aging population will lead to structurally lower real economic growth in the coming decades.

- In order to allow wages, corporate profits and taxes to rise and to reduce high (government) debt ratios with nominal growth in this economic climate, policymakers will allow structurally higher inflation.

- Aging does not mean that retirees consume fewer goods and services. It does mean that retirees no longer produce these goods and services. The labour factor will therefore become scarcer. In addition, more will be demanded of the capital factor. Hence a stimulation for further automation.

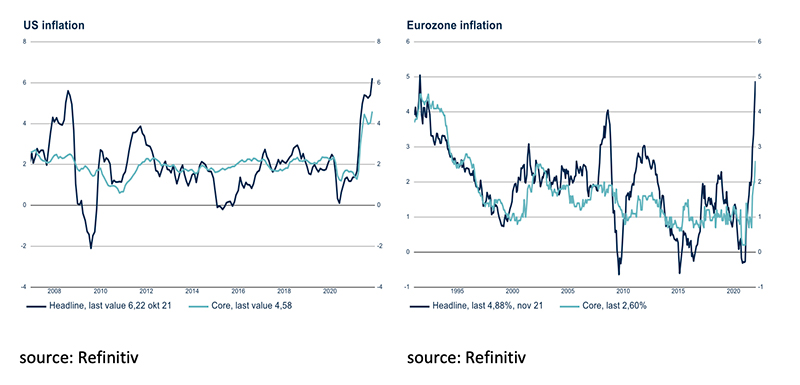

- Inflation figures in the US and the Eurozone are, with over 6% and almost 5% respectively, historically very high.

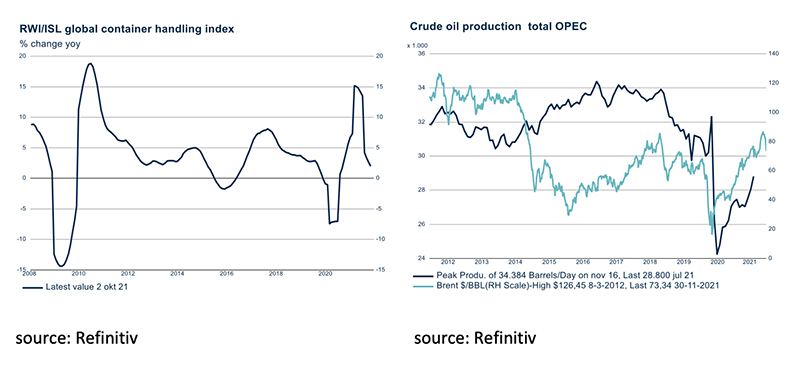

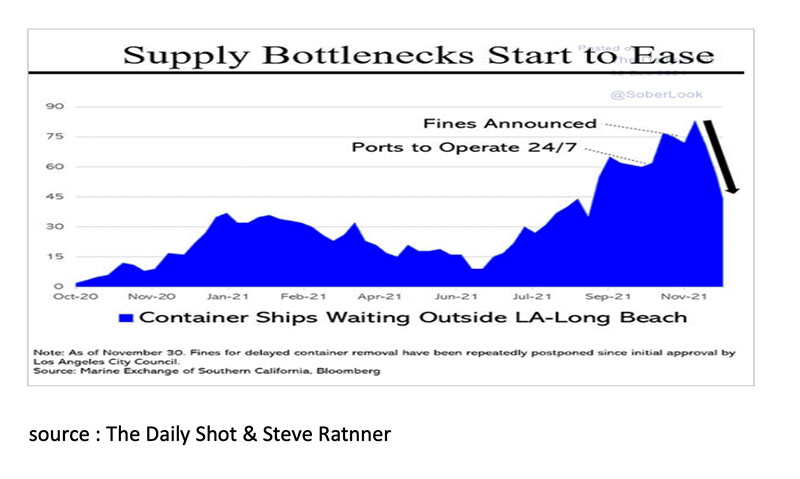

- Since the container handling index now clearly shows that many bottlenecks in the economy have already disappeared or are about to disappear and OPEC crude oil production is recovering, a substantial fall in inflation in the course of 2022 seems very likely.

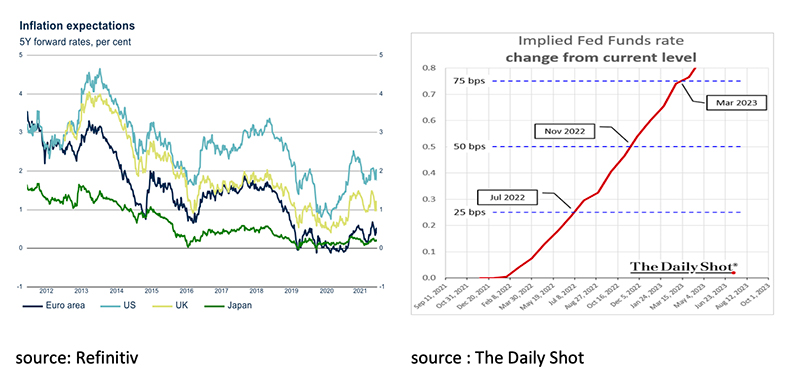

- Because the central bank's policy is to keep nominal economic growth high with very low interest rates and because inflation expectations for the longer term remain limited, we do not expect the FED or the ECB to adjust monetary policy in such a way that the economy is seriously affected by this.

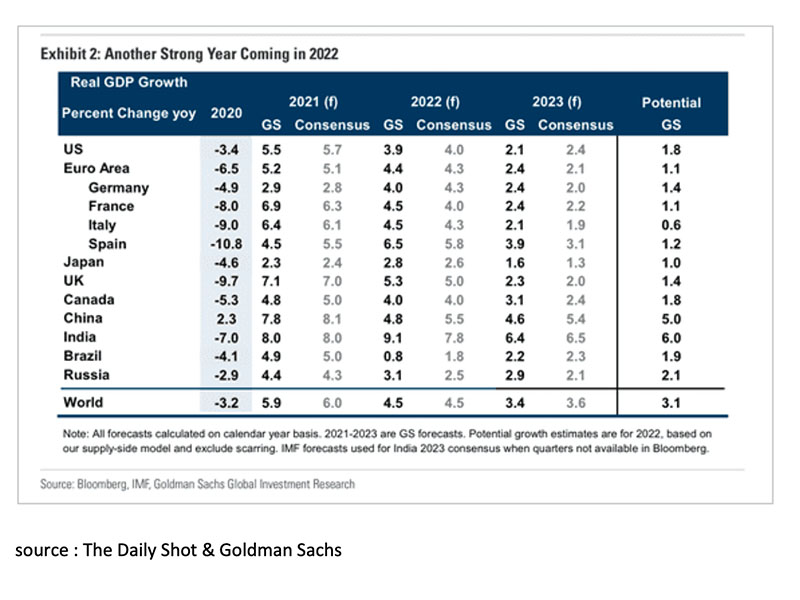

- The outlook for the global economy therefore remains positive for both 2022 and 2023 and the chance of a recession remains small.

- Despite the strong performance in 2021 (ytd), the outlook for equities remains positive in 2022.

The size of an economy is determined by two factors: 1) the number of people that work and 2) the level of their productivity. The more people work, the more goods and services can be produced. In addition, things like better education, good infrastructure, better machines and faster computers help those people to be more productive and therefore also to be able to produce more. To allow an economy to grow, it is therefore important that the number of people who work increases and/or that the people who work become more productive. This real economic growth can benefit employees in the form of higher wages, employers in the form of higher corporate profits, and/or the government in the form of higher taxes. To be able to predict the future structural real growth of an economy, it is therefore important to look at both the increase in the future (working) population and the potential increase in labour productivity.

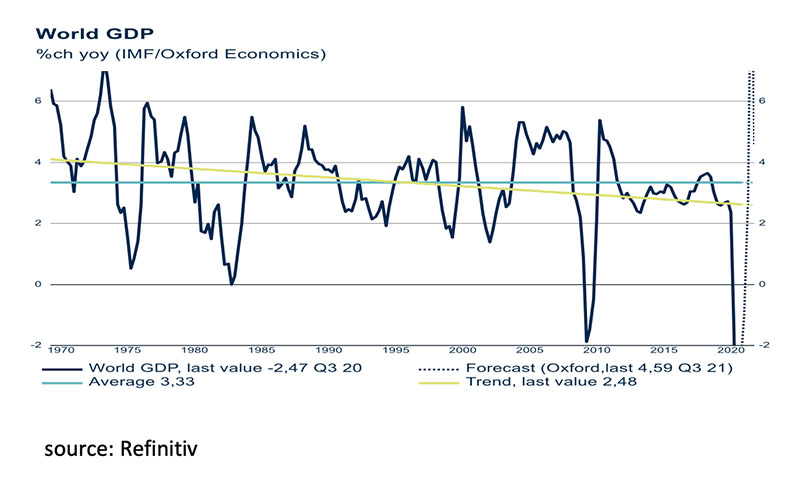

If we first look at the growth of the world economy since 1970, we see that real economic growth over that period averaged +3.33%. However, we also see that the trend growth of the world economy has structurally decreased from +4.1% in 1970 to +2.48% in 2021.

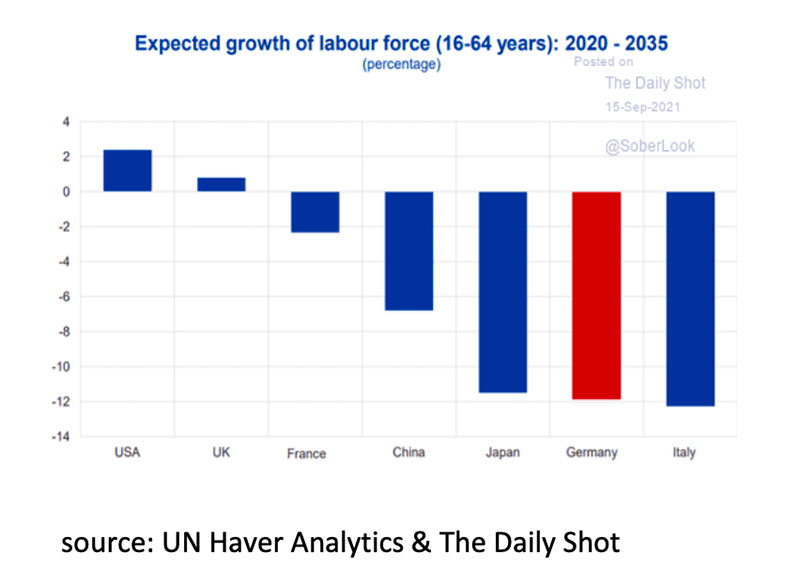

The cause of this structurally lower real economic growth is both a decrease in (growth of) the labour force and a decline in the increase of labour productivity. Below we see that in major countries such as France, China, Japan, Germany and Italy the percentage of employed people is expected to decrease between 2020 and 2035. The US and the UK are two positive exceptions where the labour force is expected to increase (slightly).

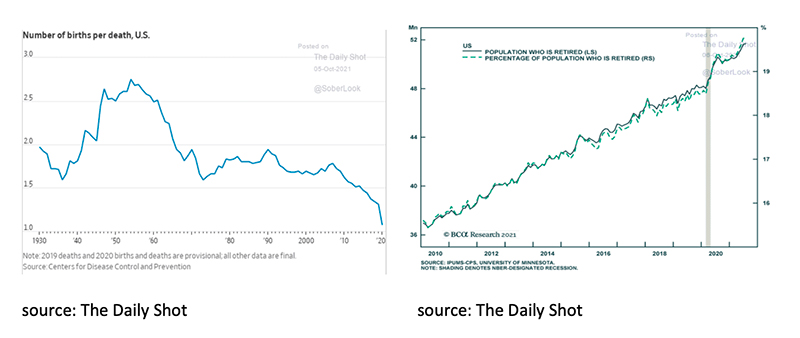

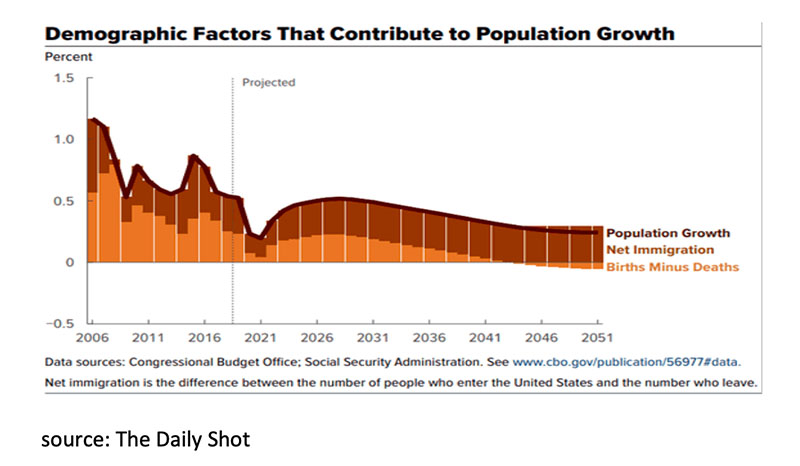

If we zoom in further on the US, we see that the number of children that are born barely exceeds the annual number of people who die and that the percentage of retirees is structurally increasing.

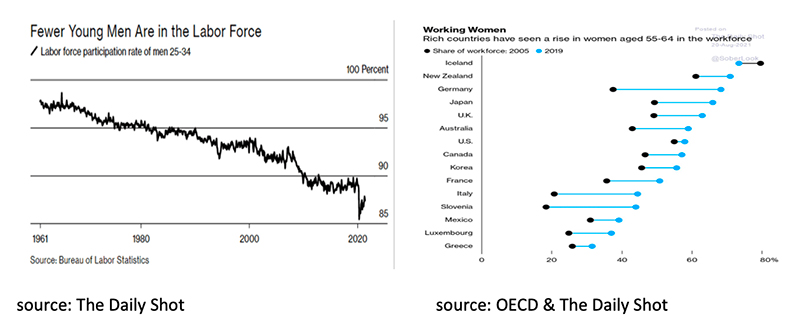

Another negative aspect is that, both in the US and in many other countries, young people are entering the labour market increasingly late. This would not be a problem if it meant that young people join later because they study longer as their labour productivity would be significantly higher as soon as they start working, thanks to the education. However, it concerns the group aged 25-34. An age at which usually most studies have already been completed.

Positive, on the other hand, is the structural increase in women's participation in the labour market, both in the US and in almost all other countries.

However, the main reason that the (working) population in the US is still structurally increasing is the relatively large number of immigrants that the US “permits” every year.

However, it should be clear that worldwide the growth of the working population is decreasing, as in the US, or even will be negative, as in countries such as Germany, Japan and China. As there are fewer and fewer additional people to put to work, real economic growth will also be structurally lower.

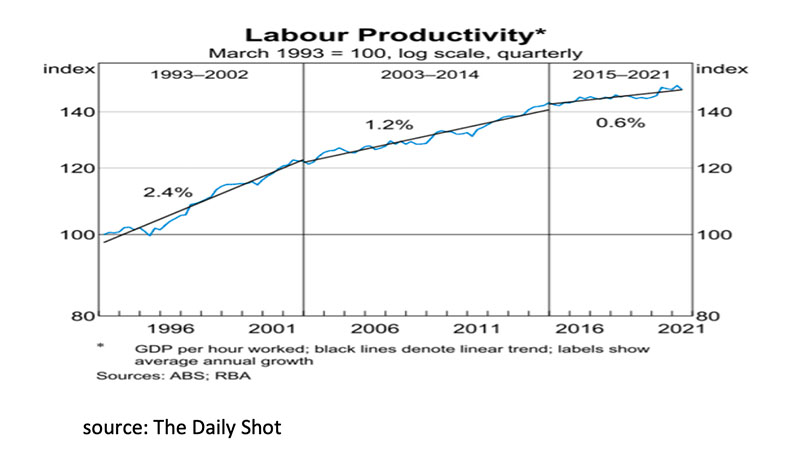

In addition, it is important for structural real economic growth what the prospects are for labour productivity. In that regard, it is good to realize that in an inefficient emerging market, it is easier to increase labour productivity with more education, better infrastructure, more powerfull machines and faster computers than in an already efficient economy such as the US, Germany or Japan. The more efficient an economy, the harder it is becoming even more efficient. A good example of this can be seen in the graph below showing the development of labour productivity in Australia since 1993. Between 1993 and 2002, labour productivity increased by an average of +2.4% annually. Between 2003 and 2014 this decreased to +1.2% and between 2015 and 2021 even to +0.6%.

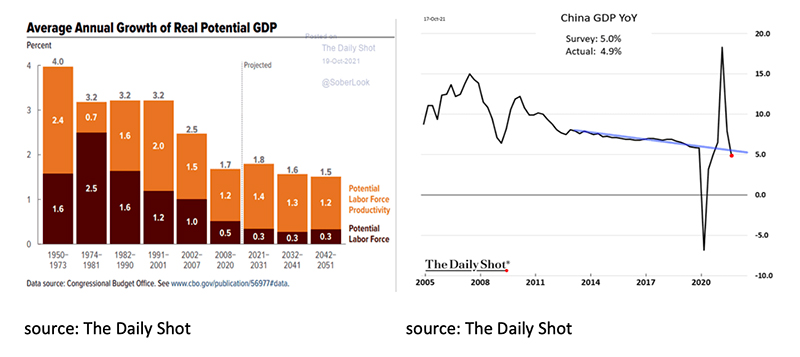

On balance, the decline in the growth of the labour force and the decline in the increase in labour productivity will lead to a structurally lower real economic growth in the world. This is clearly visible in the chart below for the US, but also applies to China, where economic growth has already declined structurally in recent years for the same reasons from a +10% annual average at the beginning of this century to a +5% nowadays.

Although in theory there are ways to structurally increase real economic growth, almost all of these solutions are difficult to realize in practice. For example, increased immigration is often seen as undesirable, as is working more hours due to a longer working week, fewer holidays and/or retiring later. On top of this, more outsourcing and globalization seem less obvious since the Covid-19 crisis. The employment rate of women is expected to increase and it may be that the increasing automation and robotization can lead to higher labour productivity. All in all, a further decline in real structural economic growth seems inevitable and policymakers will not be able to avoid allowing more inflation on a structural basis in order to continue to be able to increase wages, corporate profits and taxes in the future and so reducing high (government-) debt ratios with nominal growth. Furthermore, aging does not mean that retirees consume fewer goods and services. It does mean that retirees no longer produce these goods and services. The labour factor will therefore become scarcer, which means that wages in the future will rise more. In addition, more of the capital factor will be demanded, which means that capital investments in automation and robotization will need to increase substantially.

For both economists and investors, the month of November was mainly dominated by concerns about the new Covid-19 variant Omicron, the high inflation data and imminent changes in the monetary policy of the FED and ECB. Although the Omicron variant seems more contagious than the Delta variant, much is still unclear. However, the economy in both the US and the Eurozone now seems more resistant to Covid-19 and policymakers are better prepared, making new severe lockdowns like a year ago unlikely. More worrisome for the economy are the recent high inflation figures and its possible impact on the monetary policy of both the FED and the ECB. This is even more so as the current debt-laden economy is unable to sustain a substantially higher interest rate. If we look at the inflation figures in the US and the Eurozone, we see that year to date they increased by resp. over 6% and almost 5% and are also very high from a historical perspective. A response from the Central Banks therefore seems inevitable.

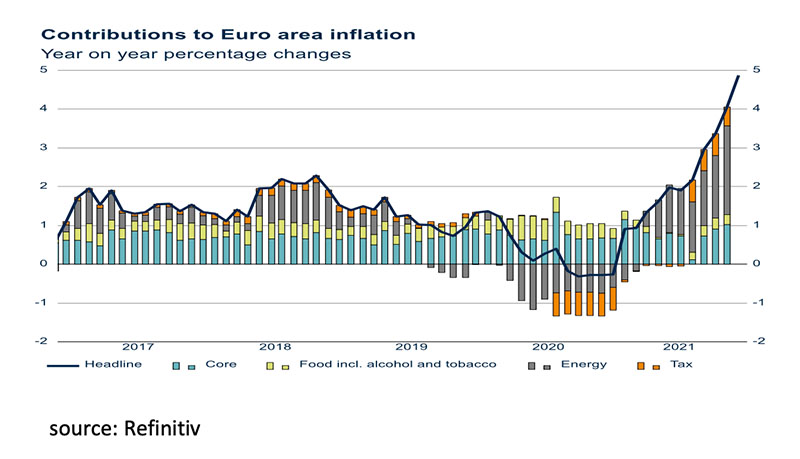

However, if we zoom in a little more on the inflation figures, we see in the Eurozone that the increase in the inflation figure is almost entirely caused by higher energy prices and higher taxes.

Since the container handling index now clearly shows that, just as with the economic recovery after the banking crisis of 2008, most bottlenecks in the economy are gradually disappearing again and OPEC crude oil production is recovering, a substantial decline in inflation in the course of 2022 seems very likely once higher energy prices and taxes disappear from year-on-year comparisons.

Because the policy of Central Banks is aimed at maintaining high nominal economic growth at very low interest rates and because inflation expectations for the longer term remain limited, we do not expect the FED or the ECB to change monetary policy in 2022 in a way that the economy is seriously affected by this.

The outlook for the global economy therefore remains positive for both 2022 and 2023 and the chance of a recession remains small.

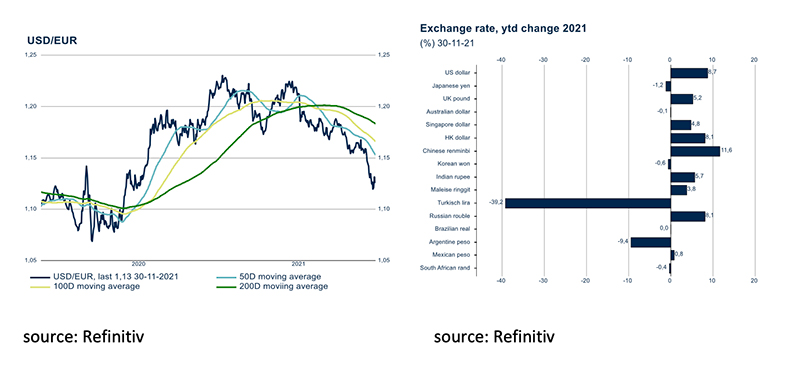

The US dollar increased by almost three percent against the Euro in November, bringing the increase in 2021 to +8.7% (ytd). The US dollar has also become more expensive compared to most other currencies in 2021. The Chinese Renminbi, heavily controlled by the government, is one of the few exceptions.

The US dollar mainly benefited from the strong US economic recovery, lower Covid-19 infection rates in the US compared to the Eurozone and the expectation that the FED will tighten monetary policy in 2022.

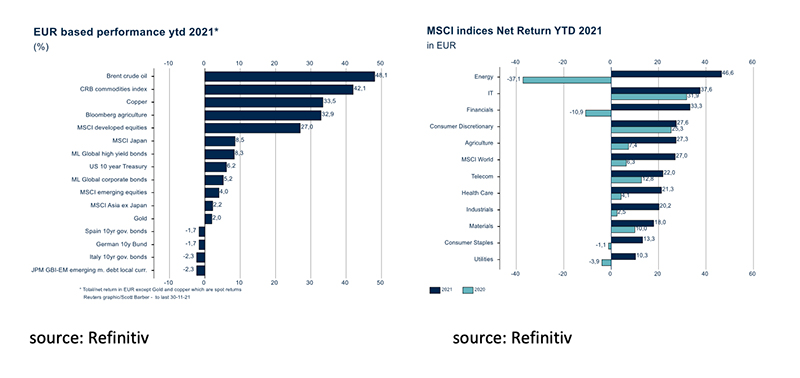

Despite the correction in November (-5.1%), Commodities remain the asset class with the highest return in Euro at +42.1% (ytd). The return on Equities (MSCI Developed Equities) rose to +27.0% (ytd) in November (+0.6%) thanks to the US Dollar. Within Equities, the energy sector remains the sector with the highest return at +46.6% (ytd) in Euro. Negative returns (ytd) were only achieved on European government bonds and Emerging Market Debt in Local Currency. Within the MSCI Developed Equities Index, all sectors achieved returns of +10% (ytd) or more.

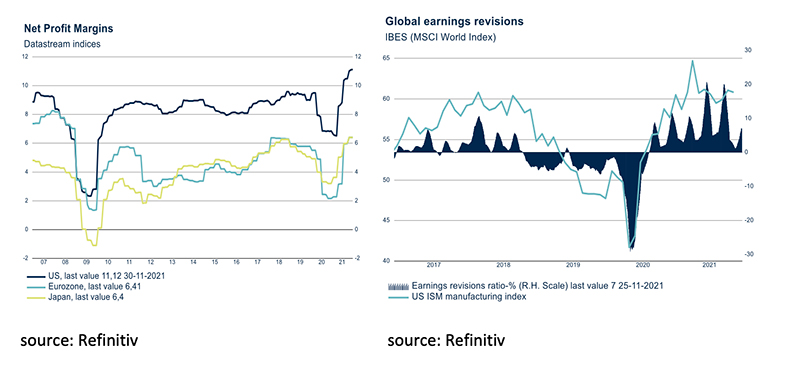

Despite this strong performance in 2021 (ytd), the outlook for equities remains positive in 2022. While Central Banks such as the FED and ECB may tighten monetary policy slightly in 2022, they will continue to ensure that nominal economic growth is kept relatively high. In addition, the underlying fundamentals for companies also remain good, due to the high economic growth and the high profit margins. On top of this, corporate profits continue to surprise positively.

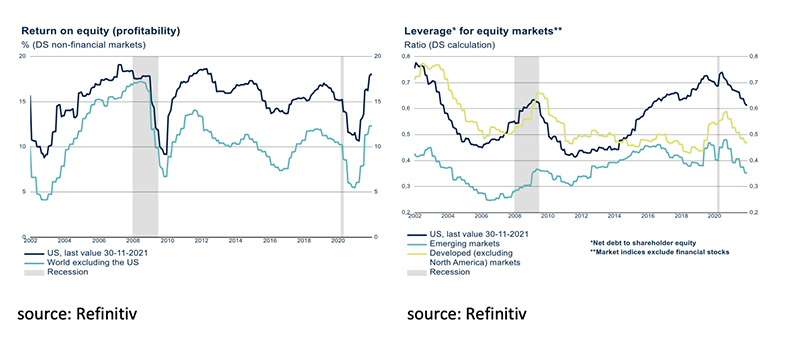

In addition, companies are still seeing their return on equity rise and their leverage is still falling.

Government bonds (10 years) in both Germany and the US are, with a yield of -0.34% and 1.43% respectively, still not a good alternative. Especially considering the current inflation (Nov. ’21 yoy) of 5.3% in Germany and 6.2% in the US. Compared to this, credit spreads on High Yield (+4.03%) and Emerging Market USD Debt (+3.52%) bonds offer more protection against currency depreciation.

Like equities, Commodities will continue to benefit from the ongoing economic recovery in 2022 and 2023. However, the prices of a number of Commodities, such as energy, will return to normality as bottlenecks gradually disappear and oil-producing countries ramp up production again. It is therefore important to distinguish between raw materials that continue to benefit from increasing demand and raw materials that have temporarily benefited from bottlenecks caused by Covid-19, like oil.

Disclaimer: While the information contained in the document has been formulated with all due care, it is provided by Trustmoore for information purposes only and does not constitute an offer, invitation or inducement to contract. The information herein does not constitute legal, tax, regulatory, accounting or other professional advice and therefore we would encourage you to seek appropriate professional advice before considering a transaction as described in this document. Any reference to third parties does not constitute an advertisement neither implies an affiliation with Trustmoore. Therefore, no liability is accepted whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from the use of this document and from any reference to third party’s articles or opinions. The text of this disclaimer is not exhaustive, further details can be found here.