- Most countries show high vaccination rates and with that, economic activity surges. But loosen too fast and infections surge again... Apparently some restrictions are still needed.

- With increased vaccination rates comes world economic activity.

- Eurozone gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to grow > 5 % and the US > 7 % to return to pre-pandemic levels by the end of the year.

- Europe (ECB) will now allow overshoot in inflation following the example set by the FED. Both are giving justification for sustaining ultra-loose monetary policies for much longer.

- The FED’s first baby steps in June towards tightening did not bode well for markets reaction so are we in a place of no return?

- US job reports were strong until start of July. Hence markets retreat from record-high levels for now and await Q2 results from companies to come.

- OPEC+ talks fell apart but spat is likely to be resolved sooner than later.

- Upcoming shortages will be offset by more production eventually and offset inflation risk.

- US shale on track for one of the best years. Oil prices above USD 70/barrel unleash high potential for US shale.

- Higher oil prices will be temporarily and do not stop economic recovery.

- What about inflation? Not, if it was up to the bond markets (which are always leading).

- US 10-year Treasury yield has fallen to unexpected low levels again of 1,33 % with the 10-year Bund yield following to more negative territory levels of -0,31 %.

- With current inflation, real yields are even worse and especially the yield on corporate high yield bonds has dropped below inflation, making it extremely unattractive to invest in.

- In a nutshell the economy is powering ahead, The FED keeps on buying Treasuries and mortgage back securities, cash is abundant with USD 750 billion on the sideline. Real assets like (private) equity, real estate, infrastructure related, alternative investments and commodities are still in demand as a diversifier for portfolios.

- Asia and especially China is much overlooked by investors to allocate money into it, but the market capitalization keeps on growing.

- Our special topic of the month dives into this issue and puts China in the spotlight.

- The economic recovery is great for banks. The financial sector is amongst the cheapest.

- After 23 US banks passed the latest stress test the FED allows banks to pay out dividend again and resume buying back their stocks and thus removing all coronavirus pandemic restrictions.

- Europe’s banking sector is not in the same shape, and it might take longer to follow. Still, expect some preliminary interest in the European financial sector.

- Robinhood is eyeing a USD 40 billion IPO in July. Does this take us back to the dotcom crisis in 2000?

- Value investors had a great run in 1HY2021. Don’t rotate back into growth and tech yet. Our assumptions are that there is still space left for value stocks.

- After the G7 established groundbreaking results in their aim to elevate minimum corporate taxation to 15 % on a worldwide basis, 130 countries reached an agreement as well on re-allocation of profits and minimum tax rates. For now, only limited for large corporations but still. We do not expect fast changes for corporates and countries yet.

- Biden will sign executive order aimed at Big Tech business forcing them to open up for small businesses to enter.

- The volatility in crypto currencies remains. Some dropped to zero.

- When hackers are to be paid in Bitcoins it does not bode well for the immediate future of these currencies. Furthermore, China continues to push out crypto from their economy.

The US versus China: an irresistible force versus an immovable object.

Summer holidays are upon us and provide us with a break from the inflation and interest debate and look at topics we may remember 10 years from now.

When the investment community debated over the 2001 Argentine default, Louis Gave from macro-economic research house Gavekal in Hong Kong pointed out that the entry of China to the WTO would probably have a bigger impact in 10 years’ time. Who remembers Argentina today? Arthur Kroeber, head of research from Gavekal Dragonomics, points out in this article the irresistible force versus the immovable object, that a new chapter is going to be written in the relationship between the east and west.

Henk van Eldik, who is representing Gavekal research and funds, with his own company specialized on quality research and boutique asset managers, has summarized Arthur’s arguments for our readers and also provides some investment thoughts.

President Biden is striking a pugnacious tone with China. At the last G7 summit, he renewed his call for the world’s democracies to take joint action to oppose Beijing’s alleged use of forced labor in Xinjiang, and to fund an alternative global infrastructure program to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. At home, he has used the specter of Chinese competition to justify big government investments in infrastructure and R&D. But even as Biden keeps rattling the sabers he inherited from Donald Trump, trade, technology and investment flows between the world’s two biggest economies remain resilient. Which matters more, economic data or political bad-mouthing?

As Gavekal noted a few years ago, US policy on China is now defined by a struggle between an irresistible force and an immovable object. The force is the US government’s desire to tame the threat to national and economic security it sees from a rising China. The object is the financial interests of multinational companies in China This conflict will be a permanent feature of the global landscape over the next decade.

Biden and his team have accepted Trump’s core policy innovation: that America’s stance towards China is no longer “constructive engagement,” but strategic competition. Trump essentially catered to two groups: national-security hawks worried about China’s rising technological and military might, and economic nationalists who wanted to re-shore as much traditional industry as possible and conduct trade policy in a purely unilateral way.

Biden evidently wants to satisfy these groups, but has added a third: a “democratic values” constituency, which would like to stem the supposed advance of authoritarianism of which China—by virtue of its economic success—is the most effective exponent.

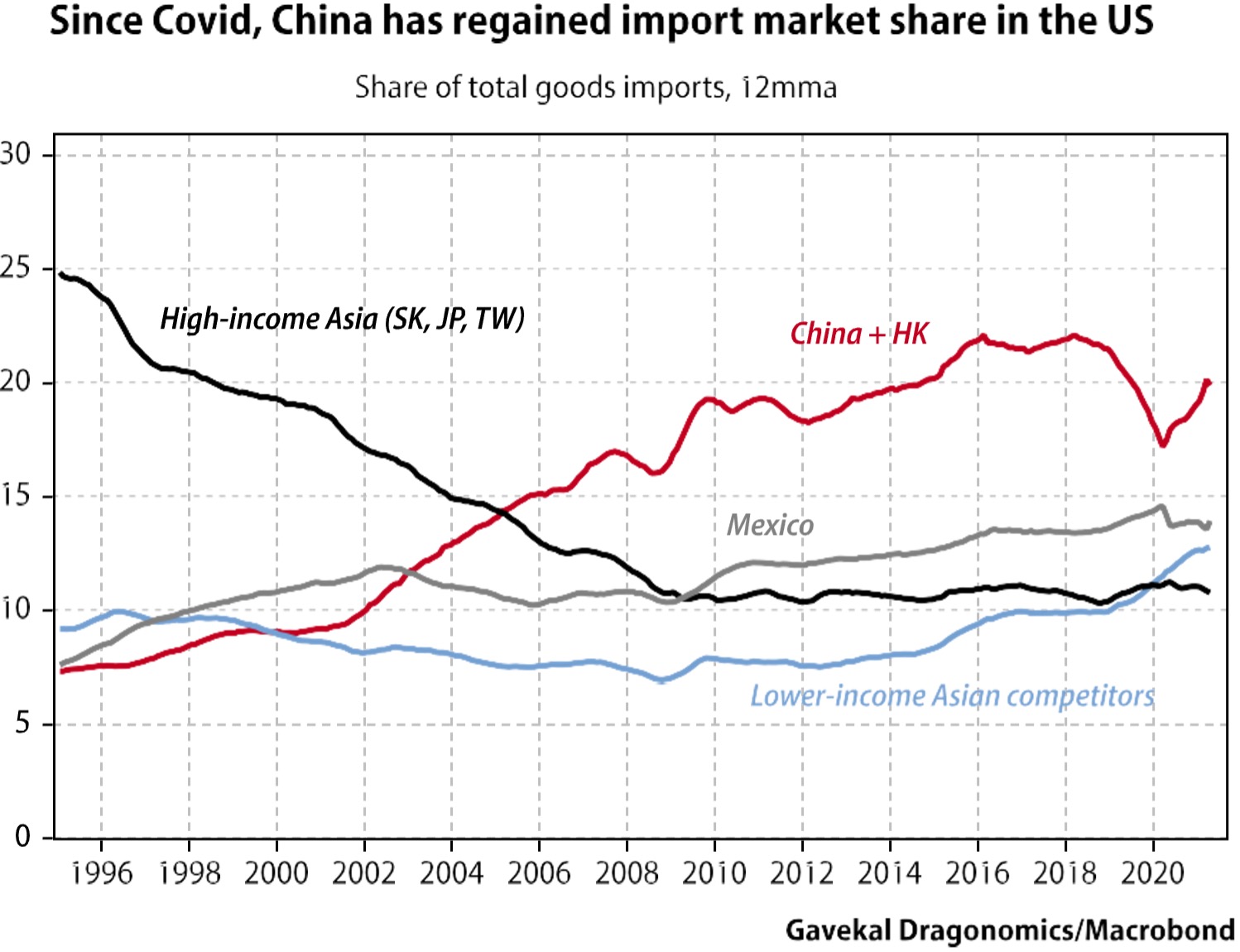

The other major interest group that Biden could address—or at least be constrained by—is the business and financial community. Despite complaints about Chinese regulation, multinationals generally see access to China as essential to their global competitiveness. China is a big, fast-growing market with a uniquely efficient and resilient production base—a virtue underscored last year, when China contained Covid, swiftly returned its production chains to normal and regained half of the US import market share that it had lost during the trade war.

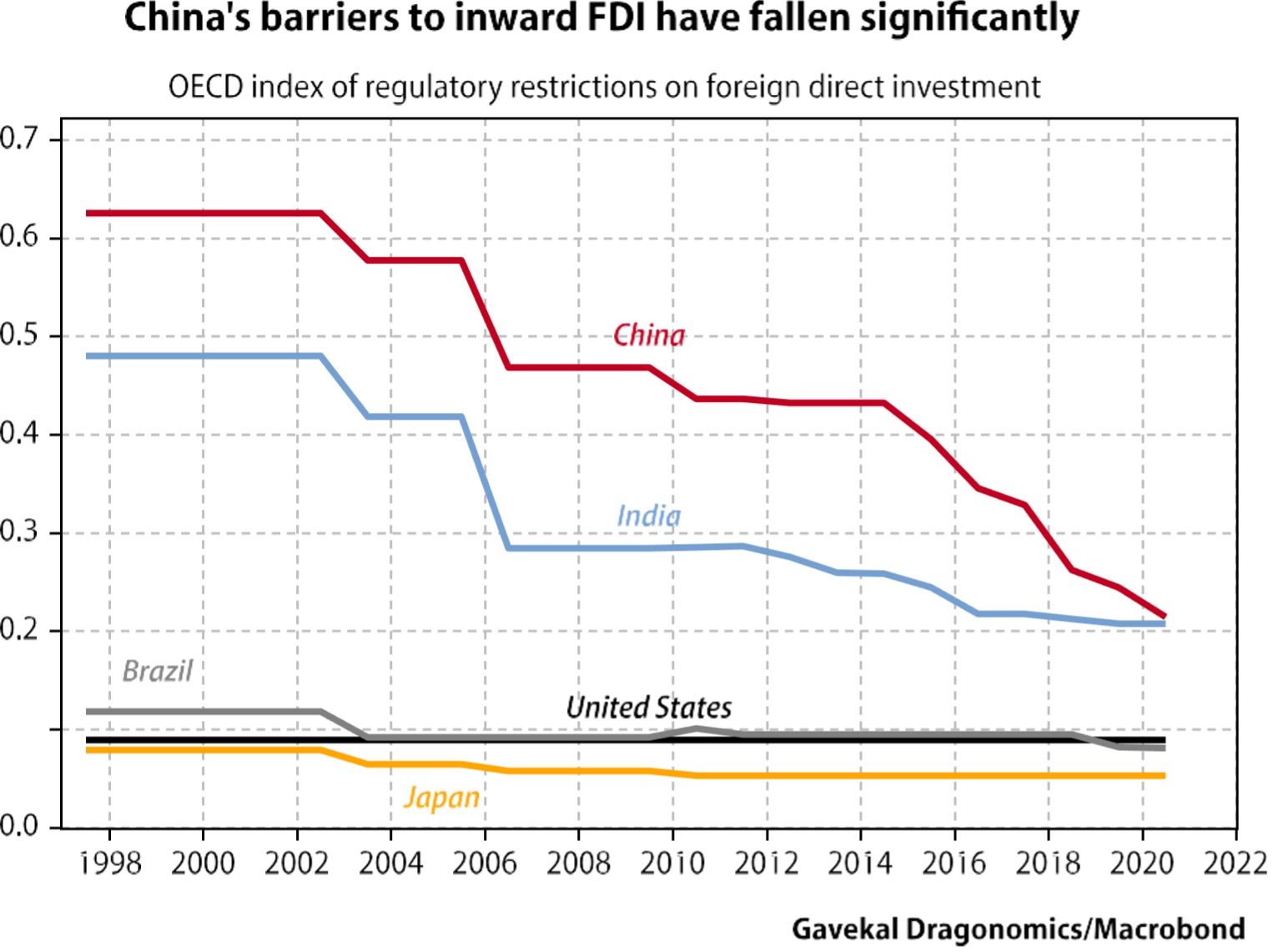

China knows these strengths and wants to keep multinationals on site because it still requires both their technology and their ability to act as a counterweight to increasingly hostile politicians in Washington.

For financial institutions, the logic is equally compelling. China now accounts for about 17% of the world economy. In aggregate, the weight of China in global financial portfolios has decreased. China represents just 3% of the total foreign equity holdings of US investors, and 1% of foreign bond holdings.

The other way of understanding the Biden strategy is to think about the possible three responses of a country like the US to the rise of an authoritarian mercantilist power like China:

1) act to harm or hinder China.

2) act with allies and multilateral mechanisms to constrain China’s ability to maneuver.

3) act at home to strengthen the US capacity to compete

Spending money on R&D and industrial policy to counter a supposed Chinese threat jibes with Biden’s broader interest in a bigger government role in the economy. The Innovation- and Competition Act, recently passed by the Senate, authorizes US$250bn in funding for R&D and tech industry support, and clearly reflects the administration’s priorities.

Working with allies is a constant talking point but faces constraints. Nonetheless, Biden has mended some fences with Europe, notably by crafting an agreement over a global minimum corporate income tax and resolving a long-running trade dispute over subsidies to Airbus and Boeing. The latter seems driven by concern that China’s aircraft maker COMAC could become

a serious competitor in several years and that the US and EU have a common interest in beating it back.

Biden’s first substantive regulatory action against Chinese firms came in a June 3 executive order refining a Trump-era ban on buying shares of Chinese companies with alleged military ties.

The new rule is tighter in its definition of the activities of concern, which are defense and surveillance. This greater clarity may make it easier for US investors to keep raising their exposure to Chinese equities without having to worry as much about falling afoul of a blacklist.

These actions could indicate that Biden is trying to strike a balance between national security and business interests, by establishing narrower definitions of what is off-limits and more predictable rules about how restrictions will be imposed.

None of this means that uncertainty has been banished. Quite the reverse: uncertainty is now baked in. There is an acute and permanent tension between the goals of national security, economic self-sufficiency, and democratic values on the one hand, and maximizing China-related business opportunities on the other. The forces arrayed on both sides are powerful. The pressure to impose new controls on technology and financial flows will rise as the 2022 midterm elections approach. The US-China relationship will be much less erratic under Biden than under Trump, but it is still far from finding a stable equilibrium point.

In terms of investment opportunities, one should probably look less at obvious names as Tencent and Alibaba stocks which are presented in every Global or EM fund also because the Chinese government requires these Internet companies to follow the same rules as regular Chinese companies. Huawei, on the other side, is a good China play and active in many areas.

Having said that, western MNC which derive the majority of their (future) growth from domestic China may soon become quickly unattractive unless they operate in the areas where China is looking to develop its domestic market like financial services and asset management. This means that MNCs can still produce in China, but their access to the Chinese domestic market will be limited and in time overshadowed by Chinese names favored by Chinese consumers.

Contrary to the US where the FED will always save the equity holders, China will protect the savers and bond holders which can be found back in the fact that China still has positive interest rates and no intentions to go the western way. China has a large toolbox to play with which is often underestimated by western commentators, only looking at China through the western policy glasses.

The proof of this was found in the March 2020 correction, where Chinese bonds were the only safe heaven as US Treasuries went down with equities. Today, Chinese bonds remain underrepresented in the Global Bonds indexes whereby the stock continues to grow also in green and blue bonds.

Disclaimer Clause: While the information contained in the document has been formulated with all due care, it is provided by Trustmoore for information purposes only and does not constitute an offer, invitation or inducement to contract. The information herein does not constitute legal, tax, regulatory, accounting or other professional advice and therefore we would encourage you to seek appropriate professional advice before considering a transaction as described in this document. Any reference to third parties does not constitute an advertisement neither implies an affiliation with Trustmoore. Therefore, no liability is accepted whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from the use of this document and from any reference to third party’s articles or opinions. The text of this disclaimer is not exhaustive, further details can be found here.